Thursday, June 30, 2005

A Divine Touch

A month ago, this blog had a piece on Steven Benner, biologist from the University of Florida, and one of the pioneers in the field of synthetic biology.

Benner is seeking to build in his university lab brand new life, or as he put it, "artificial biochemical systems that reproduce the complex behavior of living systems, including their genetics, inheritance, and evolution." He said:"The ultimate goal of a program in synthetic biology is to develop chemical systems capable of self-reproduction and Darwinian-like evolution."

Yet now it looks that Benner might be a little late from the gate.

Yesterday the Wall Street Journal ran a fascinating story about J. Craig Venter, the innovative biologist who tied the U.S. government in decoding the human genome in 2000.

Now Venter has launched a new company, called Synthetic Genomics Inc., whose goal is, he told the Journal, the creation of the first "human-made species." The company, which is funded by $30 million from "several weathly private investors," as well as, interestingly, a $12 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, will first attempt to create a "made-to-order" bacterium by assembling genes like pieces of software code into a "man-made genome [that] would be installed inside a bacterium whose own genes have been removed."

Venter says that such frankenstein bacteria could start new ways of industrial production of drugs, chemicals, and energy, like ethanol.

Venter believes, the Journal says, that by creating such lifeforms he "may come closer to understanding what life is and how scientists can manipulate it for the benefit of human kind."

Venter told the paper: "This is the step we have all been talking about. We're moving

from reading the genetic code to writing it."

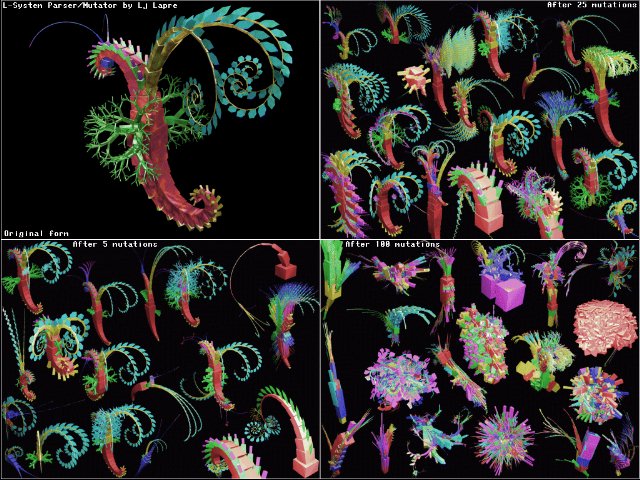

Illustration by L.J. Lapre

Thursday, June 23, 2005

Celestial Soiree

Space Daily has a great little piece on the upcoming celestial conjuction of Venus, Mercury and Saturn.

Anybody with a telescope, or at least a good pair of binoculars, should get ready at sunset this weekend when the three planets will form a tight, bright triangle above horizon. Calling it "spectacular," the report higlights some cool trivia about the event. So clutter your head:

The closest planet to the sun, Mercury, is not the hottest. Venus is. The surface temperature of Venus is 870 F (740 K), hot enough to melt lead. The planet's thick carbon dioxide atmosphere traps solar heat, leading to a runaway greenhouse effect.

Venus is so bright because the planet's clouds are wonderful reflectors of sunlight. Unlike clouds on Earth, which are made of water, clouds on Venus are made of sulfuric acid. They float atop an atmosphere where the pressure reaches 90 times the air pressure on Earth. If you went to Venus, you'd be crushed, smothered, dissolved and melted--not necessarily in that order.

Mercury is only a little better. At noontime, the surface temperature reaches 800 F (700 K).

Radars on Earth have pinged Mercury and found icy reflections near the planet's pes. How can ice exist in such heat? NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft is en route to Mercury now to investigate.

Here's one way to trick an astronomer: Show them a picture of Mercury and ask what it is. Many will answer "the Moon," because the Moon and Mercury look so much alike. But Mercury has something that the Moon does not: long sinuous cliffs called "lobate scarps." Some researchers think Mercury's scarps are like wrinkles in a raisin, a sign of shrinkage.

If you look at Venus or Mercury through a telescope, you won't be impressed. Both are featureless, Venus because of its bland clouds, Mercury because it is small and far away. Saturn is different. Even a small telescope will show you Saturn's breathtaking rings.

Galileo Galilei discovered Saturn's rings almost 400 years ago, but he didn't understand what he saw. Saturn's rings are improbably thin. If you made a 1-meter-wide scale model of Saturn, the rings would be 10,000 times thinner than a razor blade. They're full of strange waves and spokes and grooves. And no one knows where they came from.

One school of thought holds that Saturn's rings are debris from the breakup of a tiny moon or asteroid only a few hundred million years ago.

As recently as the Age of Dinosaurs on Earth, Saturn might have been a naked planet - no rings! Tiny moons orbiting among the rings today appear to be stealing angular momentum, which, given time, could cause the rings to collapse.

That's one of many questions being investigated by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004. Cassini is on a 4-year mission to study Saturn's moons (all 34 of them), rings and weather.

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

Farming Brain Cells

Researchers at the University of Florida have grown for the first time brain cells in a dish.

Field of neurons, courtesy of Laval University

Their report published in the current issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says that the scientists suceeded in growing mouse neurons in a dish. The researchers said that the "cell culture method holds the promise of producing a limitless supply of a person's own brain cells to potentially heal disorders such as Parkinson's disease or epilepsy."

Said UF neuroscientist Bjorn Scheffler: "We can basically take these cells and freeze them until we need them. Then we thaw them, begin a cell-generating process, and produce a ton of new neurons."

To be sure, the scientist can't say whether the results will be amenable to human brain therapy. They pointed out however that "if the discovery can translate to human applications, it will enhance efforts aimed at finding ways to use large numbers of a person's own cells to restore damaged brain function, partially because the technique produces cells in far greater amounts than the body can on its own," the scientists wrote in a press release.

The release also quoted Dr. Eric Holland, a neurosurgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York who specializes in the treatment of brain tumors, but who is not connected to the research. "As far as regenerating parts of the brain that have degenerated, such as in Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and others of that nature, the ability to regenerate the needed cell type and placing it in the correct spot would have major impact," said Holland. "In terms of tumors, it's known that stem-like cells have characteristics much like cancer cells. Knowing what makes these cells tick may help by furthering our knowledge of the biology of the tumor."

Field of neurons, courtesy of Laval University

Their report published in the current issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says that the scientists suceeded in growing mouse neurons in a dish. The researchers said that the "cell culture method holds the promise of producing a limitless supply of a person's own brain cells to potentially heal disorders such as Parkinson's disease or epilepsy."

Said UF neuroscientist Bjorn Scheffler: "We can basically take these cells and freeze them until we need them. Then we thaw them, begin a cell-generating process, and produce a ton of new neurons."

To be sure, the scientist can't say whether the results will be amenable to human brain therapy. They pointed out however that "if the discovery can translate to human applications, it will enhance efforts aimed at finding ways to use large numbers of a person's own cells to restore damaged brain function, partially because the technique produces cells in far greater amounts than the body can on its own," the scientists wrote in a press release.

The release also quoted Dr. Eric Holland, a neurosurgeon at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York who specializes in the treatment of brain tumors, but who is not connected to the research. "As far as regenerating parts of the brain that have degenerated, such as in Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and others of that nature, the ability to regenerate the needed cell type and placing it in the correct spot would have major impact," said Holland. "In terms of tumors, it's known that stem-like cells have characteristics much like cancer cells. Knowing what makes these cells tick may help by furthering our knowledge of the biology of the tumor."

Friday, June 10, 2005

Question of Quasars

Quasars are the true masters of the universe. For no object in the whole astral menagerie packs more power than they do.

They don't look like much in telescopes, but probe one closer and you'll see the most awesome object in the universe. Quasars, which were first discovered by radio astronomers in the 1950s and hence their name, Quasi-stellar Radio Sources, are an amalgam of everything the universe can offer. At the center, there's a gargantuan black hole, a billion times more massive then the sun. The black hole's maw sucks in gas and dust from a vast accretion disc and burps light, copious amount of radio waves, and jets of electromagnetic radiation. This celestial orgy is surrounded by a vast galaxy orbiting the black hole at a safe distance.

Quasars are quite old. They were around when the universe was just 850 million years old. It takes light 13 billion years to cover the distance between most quasars and us. Hence they appear in telescopes like faint dots, although they are ten trillion times more luminous than the Sun,.

Since these behemoths are so old, scientists have long wondered what happened to them and where are they today. Finally, they have some answers.

Scientists from the Virgo Consortium, a group of computational astrophysicists from European, American, Canadian and Japanese universities, have come up with the Milenium Run, a powerful computer simulation of the evolution of the universe, including the formation of galaxies and quasars. They say in a new paper published in the journal Nature that "by tracking the merging history trees of the host halos, we find that all our quasars candidates end up today as the central galaxies in rich clusters."

The Virgo Consortium says that its model also allows to "establish evolutionary links observed at different epochs” of the universe.

That's great news for proponents of the cold dark matter model (CMD), the leading theory of the evolution of the universe, observes Nickolay Gnedin, astrophysicist from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He reported in Nature that some scientists "naturally question" whether 850 million years after the Big Bang was long enough time for such gargantuan objects to form. They questioned the validity of the CMD, which describes how small, slowly moving particles of dark matter combine in larger structures in the universe, saying that the theory works too slowly and doesn't give quasars enough time to assemble.

The consortium's results put such fears to rest: "We demonstrate that galaxies with supermassive central black holes can plausibly form early enough in the standard cold dark matter cosmology to host the first known quasars, and that these end up at the centers of rich galaxy clusters today.

They don't look like much in telescopes, but probe one closer and you'll see the most awesome object in the universe. Quasars, which were first discovered by radio astronomers in the 1950s and hence their name, Quasi-stellar Radio Sources, are an amalgam of everything the universe can offer. At the center, there's a gargantuan black hole, a billion times more massive then the sun. The black hole's maw sucks in gas and dust from a vast accretion disc and burps light, copious amount of radio waves, and jets of electromagnetic radiation. This celestial orgy is surrounded by a vast galaxy orbiting the black hole at a safe distance.

Quasars are quite old. They were around when the universe was just 850 million years old. It takes light 13 billion years to cover the distance between most quasars and us. Hence they appear in telescopes like faint dots, although they are ten trillion times more luminous than the Sun,.

Since these behemoths are so old, scientists have long wondered what happened to them and where are they today. Finally, they have some answers.

Scientists from the Virgo Consortium, a group of computational astrophysicists from European, American, Canadian and Japanese universities, have come up with the Milenium Run, a powerful computer simulation of the evolution of the universe, including the formation of galaxies and quasars. They say in a new paper published in the journal Nature that "by tracking the merging history trees of the host halos, we find that all our quasars candidates end up today as the central galaxies in rich clusters."

The Virgo Consortium says that its model also allows to "establish evolutionary links observed at different epochs” of the universe.

That's great news for proponents of the cold dark matter model (CMD), the leading theory of the evolution of the universe, observes Nickolay Gnedin, astrophysicist from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He reported in Nature that some scientists "naturally question" whether 850 million years after the Big Bang was long enough time for such gargantuan objects to form. They questioned the validity of the CMD, which describes how small, slowly moving particles of dark matter combine in larger structures in the universe, saying that the theory works too slowly and doesn't give quasars enough time to assemble.

The consortium's results put such fears to rest: "We demonstrate that galaxies with supermassive central black holes can plausibly form early enough in the standard cold dark matter cosmology to host the first known quasars, and that these end up at the centers of rich galaxy clusters today.

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

See You In Infinity

John D. Barrow, a mathematics professor at the University of Cambridge, has written a playful book dealing with the consequences of infinity called The Infinite Book.

Barrow addresses and illustrates many of the mind-boggling and glorious possibilities of living in an infinite universe where everything that has a finite probability will happen merely by chance (without any supernatural meddling).

He uses the Shakespearean monkey paradox to flesh out his case. According to this paradox, a truly random and infinite universe will one day produce all the works of Shakespeare, as if created by a mob of monkeys hitting randomly the keys of a typewriter.

Barrow has ferreted out a web site simulating the simian effort called the Monkey Shakespeare Simulator. In the simulator, which launched in July 2003, time passes 86,400 times faster than real life and each monkey is assumed to press 1 typewriter key per second. In the beginning, there were 100 monkeys, and the increase in population is continuously updated. (The lifespan of a monkey is about 50 years.) As of today, the monkey record is a string of 25 keystrokes, which happen to match a line of text from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. After 2.65157 times 10 to the 49th power of monkey years, a monkey typed: "Barnardo. Who's there?

bP,Rx:E7x[)C5enduo0hdGWQelPy:gI..."

So who's out there? If the universe is truly infinite, then all of us, doing everything we've ever dreamed of, and everything we've feared the most.

Barrow addresses and illustrates many of the mind-boggling and glorious possibilities of living in an infinite universe where everything that has a finite probability will happen merely by chance (without any supernatural meddling).

He uses the Shakespearean monkey paradox to flesh out his case. According to this paradox, a truly random and infinite universe will one day produce all the works of Shakespeare, as if created by a mob of monkeys hitting randomly the keys of a typewriter.

Barrow has ferreted out a web site simulating the simian effort called the Monkey Shakespeare Simulator. In the simulator, which launched in July 2003, time passes 86,400 times faster than real life and each monkey is assumed to press 1 typewriter key per second. In the beginning, there were 100 monkeys, and the increase in population is continuously updated. (The lifespan of a monkey is about 50 years.) As of today, the monkey record is a string of 25 keystrokes, which happen to match a line of text from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. After 2.65157 times 10 to the 49th power of monkey years, a monkey typed: "Barnardo. Who's there?

bP,Rx:E7x[)C5enduo0hdGWQelPy:gI..."

So who's out there? If the universe is truly infinite, then all of us, doing everything we've ever dreamed of, and everything we've feared the most.

Thursday, June 02, 2005

Let There Be Life

Forget artificial intelligence. How about artificial life instead?

Steven Benner, a biologist from the University of Florida, is a man fundamentalists of many stripes aren't going to like. For if he's right, they'll have to close shop. Benner's one of the leaders in the field of synthetic biology. He's seeking to build artificial life, or as he puts it, "artificial biochemical systems that reproduce the complex behavior of living systems, including their genetics, inheritance, and evolution."

He's had some remarkable success. In February 2004, Benner reported in the Nucleic Acids Research journal that his team produced a system that "for the first time can mimic the natural evolutionary process living organisms undergo." Benner reported that his team "showed that an artificially created DNA-like molecule containing six gene-building nucleotides - instead of the four found in natural DNA - could support the molecular 'photocopying' operation known as polymerase chain reaction. The artificial DNA-like molecule directed the synthesis of copies of itself and then copies of the copies, mimicking the natural process of evolution as it was first outlined by Charles Darwin." (Of course, one of the evolutionary prerequisites is the ability of the evolving system to make mistakes, some of which might be beneficial. Benner's report did not address that issue.)

Here's a summary of Benner's work that will be coming down the pike:

"The ultimate goal of a program in synthetic biology is to develop chemical systems capable of self-reproduction and Darwinian-like evolution. Such systems will support a "bottom up" exploration of the chemistry behind life, telling us how catalysts and pathways work, how they are regulated, and how they contribute to overall function in natural systems. From a chemical perspective, this work will also show how chemical reactivity is distributed in "structure space", an understanding key to combinatorial chemistry and the origin of life. Work is ongoing to:

* Chemically synthesize a larger repertoire of artificial genetic components.

* Develop DNA polymerases that better handle artificial genetic systems.

* Incorporate artificial genetic systems into artificial evolution experiments.

* Develop quantitative models for chemical evolution in artificial environments.

* Generate artificial chemical systems capable of Darwinian evolution.

* Improve diagnostics, detection, and genotyping systems for practical application."

Clearly, Benner is a man to watch. Here's more details on the work of Benner Group.

Steven Benner, a biologist from the University of Florida, is a man fundamentalists of many stripes aren't going to like. For if he's right, they'll have to close shop. Benner's one of the leaders in the field of synthetic biology. He's seeking to build artificial life, or as he puts it, "artificial biochemical systems that reproduce the complex behavior of living systems, including their genetics, inheritance, and evolution."

He's had some remarkable success. In February 2004, Benner reported in the Nucleic Acids Research journal that his team produced a system that "for the first time can mimic the natural evolutionary process living organisms undergo." Benner reported that his team "showed that an artificially created DNA-like molecule containing six gene-building nucleotides - instead of the four found in natural DNA - could support the molecular 'photocopying' operation known as polymerase chain reaction. The artificial DNA-like molecule directed the synthesis of copies of itself and then copies of the copies, mimicking the natural process of evolution as it was first outlined by Charles Darwin." (Of course, one of the evolutionary prerequisites is the ability of the evolving system to make mistakes, some of which might be beneficial. Benner's report did not address that issue.)

Here's a summary of Benner's work that will be coming down the pike:

"The ultimate goal of a program in synthetic biology is to develop chemical systems capable of self-reproduction and Darwinian-like evolution. Such systems will support a "bottom up" exploration of the chemistry behind life, telling us how catalysts and pathways work, how they are regulated, and how they contribute to overall function in natural systems. From a chemical perspective, this work will also show how chemical reactivity is distributed in "structure space", an understanding key to combinatorial chemistry and the origin of life. Work is ongoing to:

* Chemically synthesize a larger repertoire of artificial genetic components.

* Develop DNA polymerases that better handle artificial genetic systems.

* Incorporate artificial genetic systems into artificial evolution experiments.

* Develop quantitative models for chemical evolution in artificial environments.

* Generate artificial chemical systems capable of Darwinian evolution.

* Improve diagnostics, detection, and genotyping systems for practical application."

Clearly, Benner is a man to watch. Here's more details on the work of Benner Group.

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

Danse Macabre

It looks like heaven is hell after all.

This whirl of dancing ghouls is a picture of Eta Carinae, a huge dying star some 10,000 light years away from the Earth. The image taken by NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope shows the convulsing star ripping to shreds its mother, the Carina Nebula, which bore it some 3 million years ago. The star is one of the Milky Way's most massive star. It's so huge, some 100 times more massive than the Sun, that it can barely hold itself together. Yet it's also one of the galaxy's youngest stars. The Sun, for example, is 4.5 billion years old.

Over the last 200 years, the star has been expelling material into space. In 1837, it flared to hundreds of times its normal brightness and disgorged about two percent of its total mass, enough to form two Suns, astronomers from the University of Texas said. NASA said that Eta Carninae might die in a supernova blast within our lifetime.

But Eta Carninae has already spawned its progeny. Burts of powerful ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds triggered by the star's paroxyms ripped apart the surrounding gas and dust and "shocked" new stars into being, NASA said. "When massive stars like these are born, they rapidly begin to shred to pieces the very cloud that nurtured them, forcing gas and dust to clump together and collapse into new stars. The process continues to spread outward, triggering successive generations of fewer and fewer stars. Our own Sun may have grown up in a similar environment."

The agency explained that "the new Spitzer image offers astronomers a detailed 'family tree' of the Carina Nebula. At the top of the hierarchy are the grandparents, Eta Carinae and its siblings, and below them are the generations of progeny of different sizes and ages."

(The false colors in the Spitzer picture correspond to different infrared wavelength, NASA said. Red represents dust features and green shows hot gas. Embryonic stars are yellow or white and foreground stars are blue. Eta Carinae itself lies just off the top of image. It is too bright for infrared telescopes to observe.)

This whirl of dancing ghouls is a picture of Eta Carinae, a huge dying star some 10,000 light years away from the Earth. The image taken by NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope shows the convulsing star ripping to shreds its mother, the Carina Nebula, which bore it some 3 million years ago. The star is one of the Milky Way's most massive star. It's so huge, some 100 times more massive than the Sun, that it can barely hold itself together. Yet it's also one of the galaxy's youngest stars. The Sun, for example, is 4.5 billion years old.

Over the last 200 years, the star has been expelling material into space. In 1837, it flared to hundreds of times its normal brightness and disgorged about two percent of its total mass, enough to form two Suns, astronomers from the University of Texas said. NASA said that Eta Carninae might die in a supernova blast within our lifetime.

But Eta Carninae has already spawned its progeny. Burts of powerful ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds triggered by the star's paroxyms ripped apart the surrounding gas and dust and "shocked" new stars into being, NASA said. "When massive stars like these are born, they rapidly begin to shred to pieces the very cloud that nurtured them, forcing gas and dust to clump together and collapse into new stars. The process continues to spread outward, triggering successive generations of fewer and fewer stars. Our own Sun may have grown up in a similar environment."

The agency explained that "the new Spitzer image offers astronomers a detailed 'family tree' of the Carina Nebula. At the top of the hierarchy are the grandparents, Eta Carinae and its siblings, and below them are the generations of progeny of different sizes and ages."

(The false colors in the Spitzer picture correspond to different infrared wavelength, NASA said. Red represents dust features and green shows hot gas. Embryonic stars are yellow or white and foreground stars are blue. Eta Carinae itself lies just off the top of image. It is too bright for infrared telescopes to observe.)